Special EN-RU Interview with the top YouTube blogger, Justinochek

Justin Hammond is a Canadian YouTube blogger with over 2 mln subscribers who came to Russia, fell in love with the country, and now teaches English through Russian on his popular channel

This is a special interview – the first half of the interview was in English, the second half was in Russian with similar questions // Это необычное интервью – первая половина интервью была на английском языке, вторая половина – на русском языке с аналогичными вопросами.

Read or watch the interview and find out: Why did he decide to learn Russian? What is the most difficult for English learners? What do American people find scary?

Прочитайте или посмотрите интервью и узнайте: почему Джастин решил изучать русский язык? Что является самым трудным для изучающих английский язык? Что пугает американцев?

Justin Hammond, also known as YouTube blogger Justin, is an English teacher who came to St. Petersburg from Toronto to study Russian back in 2016.

Джастин Хаммонд, также известный как блогер YouTube Джастиночек, является преподавателем английского языка, который приехал в Санкт-Петербург из Торонто для изучения русского языка еще в 2016 году (сейчас в Канаде).

The move to Russia is related to Justin’s education – he has a bachelor’s degree* from the University of Ottawa in Russian language and culture. On his arrival in St. Petersburg, Justin confirmed his knowledge by obtaining* his state certification at St. Petersburg State University. In 2014, Justin received a diploma for outstanding achievements* in the promotion of Russian culture and language from the Russian Embassy in Canada. Justin not only teaches Russian but also works as an English language teacher – his students include both children and adults. In Russia, Justin organizes (online) conversation* clubs and also focuses on developing speaking skills.

* Переезд в Россию (в 2016) связан с образованием Джастина – он получил степень* бакалавра Оттавского университета по русскому языку и культуре. По прибытии в Санкт-Петербург Джастин подтвердил свои знания, получив* государственную аттестацию в Санкт-Петербургском государственном университете. В 2014 году Джастин получил диплом за выдающиеся достижения* в продвижении русской культуры и языка от посольства России в Канаде. Джастин не только преподает русский язык, но и работает преподавателем английского языка – среди его учеников есть как дети, так и взрослые. В России Джастин организует (онлайн) разговорные* клубы, а также уделяет особое внимание развитию разговорных навыков.

English part of the interview // Часть интервью на англйиском

– Justin, one question about the magazine, what do you think, will it be convenient for you to learn Russian in this way? (with parallel translation)

– Yeah, it’s always hard to say actually kind of like it when there’s like a sentence in Russian and in English below it, rather than looking like… I find it hard to go left or right, left or right. But it depends on each person.

– Yeah, you see, we have usually short paragraphs – two sentences, three sentences, and not too much. And with the words highlighted.

– Yeah, awesome!

[02:08] – So what do you think is the most difficult for English learners to understand?

– I think one of the most difficult things is articles – specifically for Russian speakers, because you don’t have articles in Russian. And I think that there exists this understanding that articles aren’t important

– why do we need articles? You know, there’s just an extra thing to remember how to do.

And I think there are two points for that. The first point is, when you’re thinking about how, you know, Russians are portrayed in American media, like criminals or gangsters or mafia people that have that really, you know, scary accent. Well, really, all that they’re doing is they’re simply not using articles correctly, and that immediately make somebody sound like a stereotypical, you know, Russian person.

So, when you hear somebody say something like ‘‘I am boy’’, right? Really, that sentence is fine, and everybody understands it, but it’s because you didn’t say I am «a» boy, it all of a sudden sounds, you know, scary and threatening.

So, I think that’s sort of one point. And the other point is just using articles incorrectly can really have a massive impact on the meaning of the sentence. So I remember a friend of mine, she was Russian, and she was supposed to meet me at the airport before I left. And she was taking a taxi. And she was late to the airport. And so I was texting her saying, where are you? And she said, like, I’m sorry, I’m talking to a taxi driver. And I thought to myself, like, what do you… what do you? Why? Why are you talking to a taxi driver like, You’re late, you need to come. And what she meant to say I was talking to «the» taxi driver. And if she had said «the» taxi driver, I would understand that she’s talking to the taxi driver who drove her to the airport. Maybe she’s asking for directions or maybe she’s paying, right? But when you say «a» taxi driver, it sounds like you’re just having a chat with somebody. And given she was already late, that made it, like really anger me I was like «no, stop!». So it really does make a big difference.

Articles are tough to learn, but they will make a huge difference to make you sound like an advanced English speaker like really fast in English, if you can do them (articles).

[05:02] Interesting… And actually, what was your first experience in learning Russian? When was it?

It was probably in 2013. And I really enjoyed it. I think that first you see the alphabet. And you think that it’s going to be very, very intimidating*. However, you learn very quickly that the alphabet’s actually very phonetic and very easy to learn in Russian, that’s not the difficult part of the language. And the sounds – it was very phonetic, right? So once you learn the alphabet, you make progress very fast, but then you immediately hit a roadblock* when you get to cases*, because the concept of cases doesn’t exist in English. And so you have to learn, you know, this idea that you can change words and put them in any order that you want. And the meaning will be the same as long as you’ve used the right cases. And that’s a very foreign concept to us. So learning how to use that and understand that was really interesting.

Yeah. So maybe, for the first time, it was not easy for you to change just the words in the sentence in different orders to make a sentence correctly.

Absolutely. Very difficult, very complex.

And to understand, yes? I think a bit…

It does make understanding more difficult because people can do things in a different order. But I don’t think that it makes it so much more complex for understanding it really is just for, like, creating sentences and stuff you need to get used to. You know what people mean, because you also don’t necessarily need to use personal pronouns* a lot, because you can use things in the right case and in the right conjugation*. So you can really get rid of pronouns, whereas in English, you can’t. So it’s interesting.

[07:20] Actually, one question was from our subscriber, and your fan, Kate asked, «So why Russian? Why did Justin decide to learn Russian?» Not, I don’t know, not Spanish, not Italian, but Russian. Why did you decide this way?

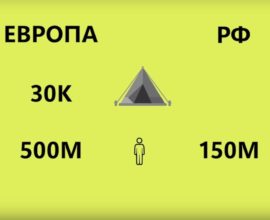

Yeah, good question. So at the time, when I started, I already knew French. And I did want to learn Spanish. But when you study a really popular language, like French or Spanish in the West, in university, for example, your classroom is like 300 people. It’s not super convenient. And so I really wanted, you know, a language where it was very different than English. Like, even if you speak English, if you look at like a Spanish text, or you look at a French text, you can still understand like 20% of it. Whereas with Russian, it was totally different. And I like that, I liked that idea. Also, I had studied Chinese before Russian, and I realized that, if I really, really want to get good in a language, I’ll have to live there for a few years. And I think I didn’t really like the idea of going to live in China, because you will always be a foreigner, in the sense of, you know, I don’t look Chinese and so wherever you go on streets, you’re always going to be treated like a foreigner. Whereas in Russia, people know if I talk to them, but generally on the street, I can just dress like normal and only wants to start having a conversation people really kind of understand. So you can feel, I think a lot more like you’re a local living there.

[09:05] Actually, and how often I don’t know maybe people treated you like a local in Russia?

How often do they treat me like a local? Often, I think, you know, it depends on the interaction, right? Like, if I go and I’m talking to a cashier*, they understand right as they hear my accent you know, but if you’re just walking around, yeah, nobody notices I think.

Questions:

What would you ask Justin about?

What are your favourite Justin’s YouTube videos?

Why do you think Justin is so popular and modest at the same time?

Grammar: Can you underline all Conditional sentences in the interview? (e.g. If I talk to them, people know that I am a foreigner)

* cases/conjunctions – падежи/спряжения (разные окончания у существительных/глаголов); pronoun – местоимение

Russian part of the interview // Часть интервью на русском:

[09:43]А теперь перейдем на русский? Небольшое Multi-lingual интервью получается!

[10:30] Что самое сложное в изучении английского* языка?

– Что касается русских, то для них самое трудное это артикли. Потому что, когда, особенно русский, человек говорит без артикля и неправильно употребляет их в английском языке, это уже показывает, что есть стереотипичный русский чувак с американского голивудского фильма, который говорит как «мафиози». Это, конечно, очень жаль… Когда человек пропускает артикль «a» – говорит “man”, вместо “a man”– это уже говорит, что это не только непервый его язык, но и говорит, что это стереотипичный вид русских в Америке. И, конечно, артикли сильно меняют значения предложения…

[11:40] Какой хороший пример ты можешь привести, связанный с употреблением артиклей?

– У меня была русская подруга в Канаде. Мы договорились встретиться в аэропорту – она мне привезла кое-какую вещь. Она ехала на такси, опаздывала в аэропорт на нашу встречу. Я ей написал сообщение, она ответила: ‘‘talking to a taxi driver’’, то есть это значит, что она, по идее, разговаривала с каким-то таксистом, а именно с тем, с которым она ехала. Поэтому я просто подумал, что она почему-то просто болтает с кем-то. Я ей ответил: «Что ты делаешь? Пожалуйста, поспеши», но она уверила меня, что она говорила именно с тем таксистом, с которым она ехала и значит, что, наверное, заплатит за проезд или просто она говорит, куда ехать. Поэтому, если бы она сказала по-английски ‘‘talking to the taxi driver’’, тогда бы это было гораздо понятнее, что она имеет в виду. Поэтому, действительно, артикли очень ценны и могут влиять на значение предложения.

[13:02] – Насколько труднее воспринимать русскую речь из-за специфического порядка слов?

– Хочу отметить, что порядок слов очень важен именно в английском языке, а в русском – не очень, потому что у вас есть падежи. Для нас, когда мы, иностранцы, изучаем русский язык, является непонятным система падежей, и когда вы меняете порядок слов, это иногда усложняет процесс понимания, что человек говорит, но не настолько, чтобы это было самой сложной вещью в обучении русскому языку. Но, всё-таки, это очень интересно и, конечно, я думаю, что русский язык в этом плане гораздо богаче, чем английский, просто потому что у вас существует безумно огромный словарный запас, но и ещё вы можете больше «играть» со словами.

[14:23] – Что труднее всего даётся в русском языке – окончания, времена, падежи или что-то другое?

– Самое сложное – запоминать, когда и куда ставить мягкий и твёрдый знаки, потому что когда я пытаюсь, например, что-то писать, и мне надо вспоминать, как это правильно пишется. При этом я всегда в замешательстве – надо тут писать мягкий знак или нет, потому что я не различаю на слух, с мягким знаком пишется то или иное слово или нет. Для меня это одинаково. Большая проблема с существительными, а с глаголами я лучше понимаю, когда они находятся в инфинитиве, что там будет мягкий знак или нет. Если это не инфинитив, то это надо запоминать…

[16:05] – Почему ты решил учить русский язык, а не, например, итальянский, французский, испанский?

– Хороший вопрос. Когда я начал учить русский язык, я уже хорошо знал французский язык, поэтому я не хотел его дальше учить. И до того, как я записался на занятия по русскому языку, я хотел учить испанский. Но у нас на Западе такая проблема – если вы изучаете такие популярные языки, как французский, испанский, то в одной аудитории в университете будет около 300 человек. Я этого не хотел, и я подумал, что если я буду когда-либо учить испанский, то тогда, когда буду жить в какой-либо испаноговорящей стране. Я раньше изучал китайский, но проблема была в том, что я не знал, что я должен был жить какое-то время в Китае, и я не хочу себя чувствовать каким-то иностранцем. Поэтому мне очень понравился русский язык в плане того, что я могу спокойно жить в Украине, в России и общаться на русском языке, не обращая внимание на то, что я – иностранец. Конечно, при общении, русские, услышав мой акцент, поймут, что я иностранец. Но я, к тому же, могу одеться, как русский человек, ходить по улицам и никто не будет обращать на меня пристального внимания…

Read, listen and watch the full interview on the web // Читайте, слушайте и смотрите полное интервью на сайте: englishmag.ru/justin-2022

The full interview available for EnglishMag subscribers

Other articles from the issue: HOW TO INSPIRE WITH A WORD // КАК ВООДУШЕВИТЬ СЛОВОМ